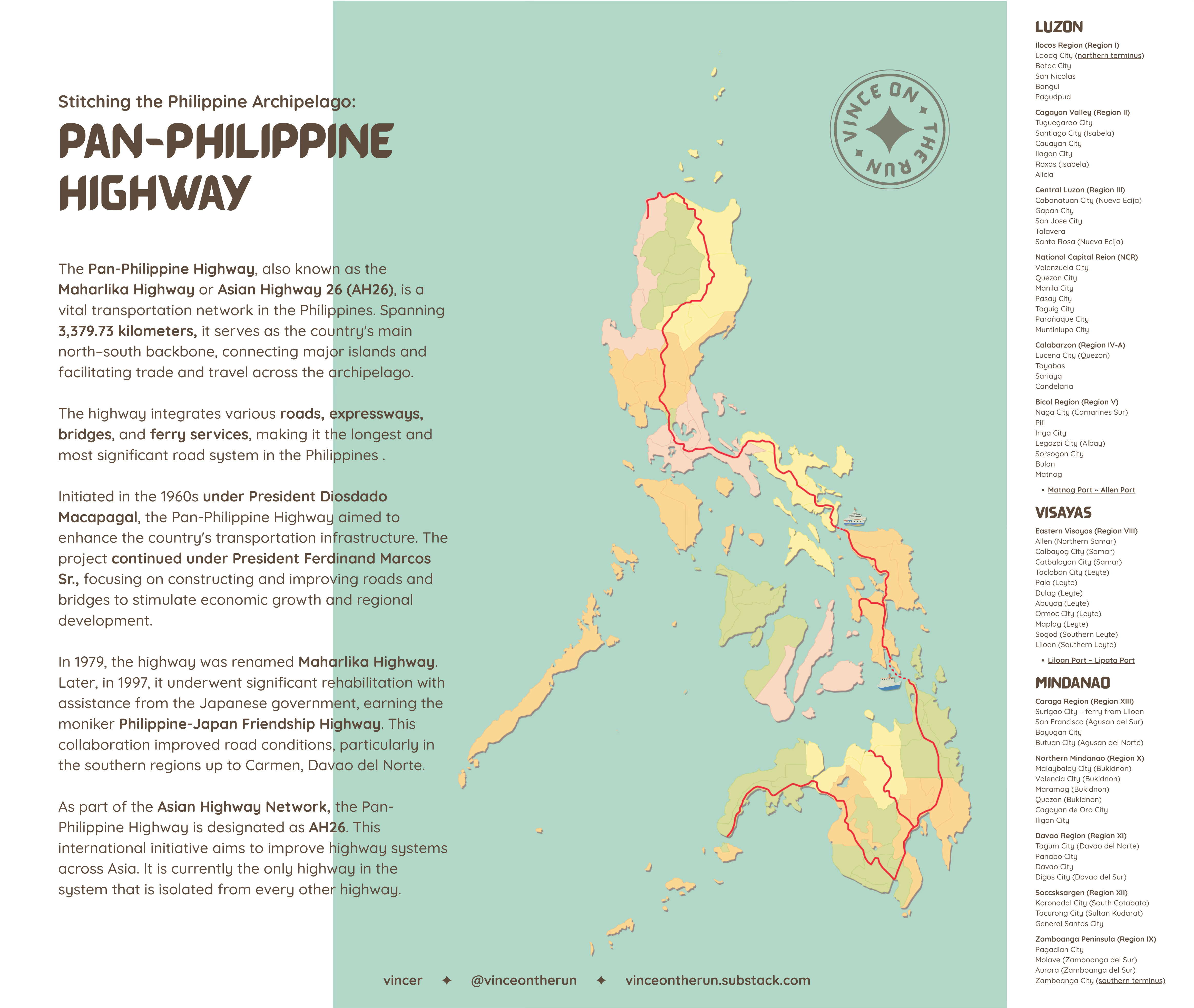

For the longest time, I’ve been obsessing over the idea of a slow, sprawling journey across the entire Philippine archipelago—one that would start at the northernmost edge of Luzon and winds its way south, back home to Davao. I reckon it all started when I got a dictionary with colored maps at the back. I spent the summer before freshman year in high school, tracing the tiny borders of countries. Placed at the center of pages 36 and 37 is the Philippines. Its principal roads etched in red like a jagged spine with a diaper. Eventually, I’ve learned that most of it form the Pan-Philippine highway, the country’s longest road, a 3,400-kilometer thread stitching together islands, provinces, and fragments of history. On paper, it's a continuous line. In reality? The gaps tell the better story.

I've mapped this route countless times. It always begins in the North—a deliberate choice, so the journey’s end brings me closer to home in Davao. From here, I’d fly to Clark, Pampanga, the northernmost airport with a direct flight from here, then take a bus to Laoag, where the highway’s northern terminus sits. From there, the plan was simple: travel south using only local transit—jeepneys, buses, habal-habal, ferries—whatever moves.

the death of a hitchhiking dream

The original vision was poetic: hitchhiking my way home, surrendering to the rhythms of the road and the generosity of strangers. While the general route would follow the Pan-Philippine highway, I would not mind the backroads and the detours. Ideally, this would be a more immersive journey. Every ride would be a conversation; every wait an observation and a lesson in patience. But the Philippines is not a country where hitchhiking thrives. Ask online forums, and the responses are unanimous: Don’t. Modernization didn’t make Filipinos more open to hitchhikers; if anything, it made us warier. I learned this the hard way, standing on a provincial road with my thumb out, watching cars slow down—only to speed up again. No matter how hard I smile to look harmless, a stranger in your car is still a stranger.

So I adjusted. If hitchhiking wasn’t feasible, I’d ride with everyone else.

the art of uncomfortable journeys

Commuting here is not for the faint of heart. It means surrendering to chaos: jeepneys that leave only when full—"when full" being a fluid concept involving chickens, sacks of rice, and at least three extra passengers squatting on the floor; Buses run on mythical schedules. If you missed the last trip, you have to spend the night somewhere in Sogod, Southern Leyte or hope for the best someone will drive you to your next destination for a price you would need to haggle. Or if lucky, you could sleep on a bench outside a sari-sari store until the day breaks. It’s a far cry from the romanticized long-haul journeys like the Trans-Siberian Railway or the iron ore train of Mauritania—those are linear, predictable. The Pan-Philippine Highway is a living thing, breathing in delays and detours.

And yet, there’s magic in that disorder. Commuting forces you into the present. You notice things: the way a jeepney driver memorizes every passenger’s stop without being told; the scent of white flower cutting through diesel fumes; the shared camaraderie when a downpour soaks everyone crammed in the back. Unlike the Western obsession with destinations—where the goal justifies the grind—Filipino commuting embodies the Taoist idea of 不虚此行 (Bù xū cǐ xíng): the journey itself is the reward. It implies that the journey’s worth isn't tied solely to the destination. Making the destination secondary; the immersion the point.

the weight of a backpack and other realities

But romanticism only goes so far. The practicalities nag at me: Can I actually do this? Walking 10 kilometers in a day is one thing; doing it in consecutive days, under the sun, with a backpack digging into my shoulders, is another. How many shirts do I pack when I sweat through them by noon? How many books can I carry without breaking my spine? (Because of course, I’ll bring books—these days, my only reading time is during my commute to work, two stolen hours where no one demands my attention.)

And then there’s the question of documentation. I forget things when overwhelmed. Will I remember the old woman who shared her suman on the bus to Bicol? The truck driver who insisted I didn’t need to pay for the four-hour ride because I made him company on an otherwise tricky but lonely route? Or that mother-daughter duo with their sako bags on their way home after the pandemic that I shared a bajaj ride with because we missed the last van in Boston to Bagangga?

Maybe that's the point. The Pan-Philippine Highway isn't one road but a thousand—some paved, some imaginary, all leading somewhere worth seeing precisely because no one told you to look.

why maps kinda lie (and why i love them anyway)

I’ve spent hours tracing routes on maps, but I’m no maphead. Maps are seductive in their simplicity. They reduce the world into clean lines and labeled dots, suggesting order where none exists— but the Philippines resists that. Towns share names (you need to be clear which San Fernando in Luzon you actually mean); roads vanish into rivers; ferries replace highways. The Pan-Philippine Highway is less a single route and more a suggestion, a patchwork of paved stretches and dirt paths. A route that looks straightforward on-screen becomes, in reality, a puzzle of jeepney transfers, habal-habal rides, and hopeful questions to locals: “Saan po ang sakayan papuntang…?”

The deeper irony is that some of the most fascinating places don’t appear on maps at all—at least, not in a way that hints at their significance. You might zoom in on a nondescript stretch between provinces, only to later learn what you missed: like the crumbling Spanish-era bridge in Laguna, Puente del Capricho, which Rizal wrote about in El Filibusterismo. Google Maps would pin the site but will not warn you about the dump site you have to pass through to get there. Mapping this trip has taught me about the country in a way guidebooks never could. It’s revealed the gaps—literal and metaphorical—between places, the way infrastructure bends around geography and politics.

Travel blogs and YouTube videos amplify the same few spots—the picturesque waterfalls, the "hidden" beaches now overrun with influencers. But the real stories live in the gaps: the kanto in Lucena where drivers trade stories while waiting for passengers, the Samar carinderia truckers detour 30 minutes for (no GPS pin, just word-of-mouth), the Quezon backroads where hand-painted signs say "Dito ang daan" because someone knew you'd get lost.

Maps lie, but that’s what makes them beautiful. They’re not just tools—they’re invitations to get lost. When you rely solely on them, you miss the lived geography: the shortcuts known only to tricycle drivers, the unlisted boat trips you need to chance upon, the fact that “10 kilometers” in the Philippines could mean 30 minutes or 3 hours, depending on the time of day.

The detours forced by these omissions become the trip’s real highlights. An impromptu stopover in Camiguin might lead you to a fiesta in some barangay along the road, where you attend a sayawan at the community basketball court. A broken-down jeepney could strand you in a town where the only lodging is a family’s spare room—and by morning, you’re part of their almusal chatter.

Maps don’t account for these moments. They can’t. And that’s why I’ll keep using them, even as I learn to distrust them. The best parts of this journey will be pinned and labeled on my Google map— the nameless places I stumble into, precisely because no one thought to document them.

the journey is the point

In the end, this trip isn’t about reaching Davao. It’s about the barker who yells “Kulang pa isa!” like a war cry, the tricycle driver who charges you triple because “Ay, layo, nong!”, the stranger who lets you charge your empty phone in her tindahan for free because you’re a visitor. It's about learning that "Malapit lang" could mean anything from 500 meters to three towns over. It's about realizing our highways, like our islands, are both connected and profoundly separate—and that the space between is where you'll find the Philippines that postcards never show.

Will I survive it? Maybe. Will it be worth it? Absolutely. Because the beauty of this archipelago was never in the maps—it’s in the messy, sweaty, unpredictable act of moving through it, and the detours they couldn't predict.

See you on the road!

⋅˚₊‧ ଳ ‧₊˚ ⋅

vincer ✦